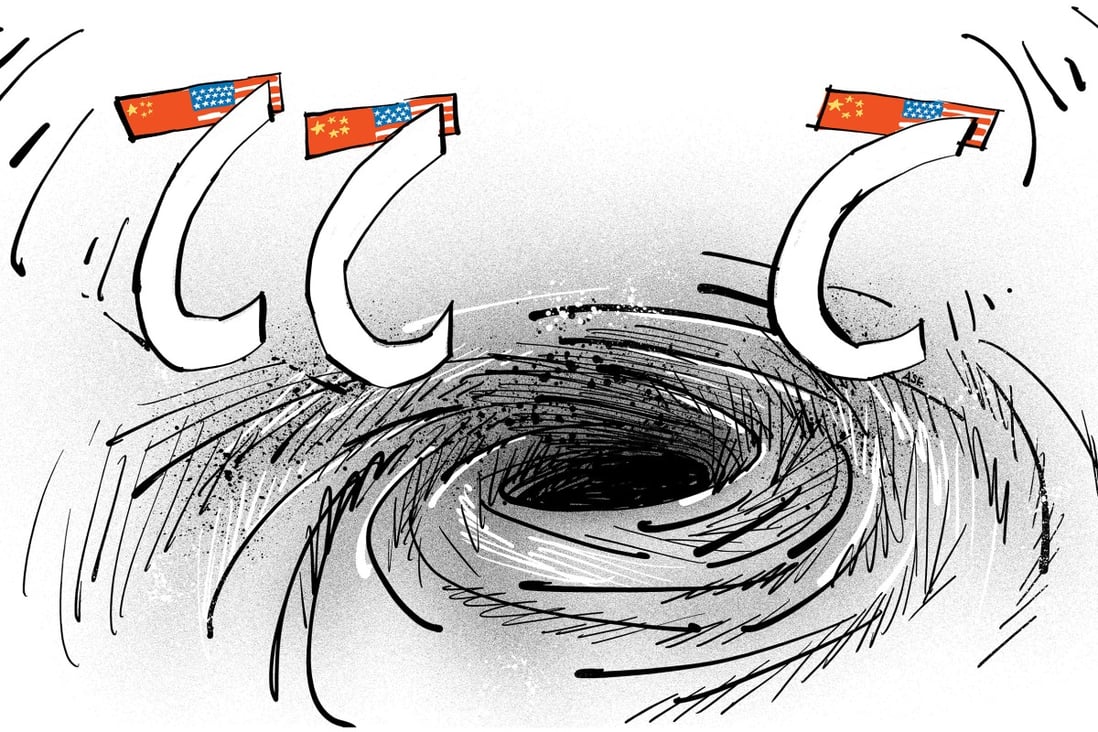

The message cannot be clearer. The world’s second-largest economy will cooperate with, compete with, and confront the No 1 economy on its own terms. Thus, the ongoing trade and tech wars could well linger on and the respective consulates in Houston and Chengdu may well remain closed.

In addition, not only is China’s relationship with the US deteriorating rapidly, relations with the likes of Australia, Canada and Lithuania are also quickly turning frosty.

For the US, competition with China has become the top priority. As a result, China has often been singled out as a convenient target or used as an expedient excuse in the crafting of numerous US laws and policies.

SCMP Global Impact Newsletter

By submitting, you consent to receiving marketing emails from SCMP. If you don't want these, tick here

Worse still, US competition with China is increasingly taking on the feel of its Cold War with the Soviet Union. During the Trump era, the US repeatedly accused China of being the source of Covid-19 after claims that the virus leaked from a lab in Wuhan. It also accused China of using forced labour and committing other human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

This year, the US announced the Aukus deal – an agreement with Britain to provide nuclear submarines to Australia – and a diplomatic boycott of the upcoming Winter Olympics in Beijing.

The US has also stepped up its activities in China’s backyard, increasing its presence in Taiwan, the South China Sea and the Indo-Pacific region, and flexing its military muscles either individually or jointly with allies.

In China’s eyes, the Trump and Biden administrations have been the drivers of rising tensions across the Taiwan Strait. Thus, US behaviour with regard to Taiwan has destroyed American credibility and removed any chance that its pledges to uphold the “one China” policy will be taken seriously. As a result, Beijing must prepare for the worst.

Similarly, China had no choice but to respond after the US sanctioned Chinese officials in Xinjiang over alleged human rights abuses. Beijing chose to sanction four members of the US Commission on International Religious Freedom, under its Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law that was adopted in June, accusing them of lying and making false statements.

However, even though competition and confrontation have dominated the US-China relationship in the past few years, 2021 did witness some rare collaboration in areas such as climate change. Surprisingly, the two sides issued not one but two joint climate declarations this year.

The first came following a meeting between US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua, in Shanghai on April 15 and 16, in which the two nations committed to cooperate on climate change.

And the US-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s, issued on November 10, states that both sides intend “to engage in expanded individual and combined efforts to accelerate the transition to a global net zero economy”.

Other positive steps in 2021 included the virtual meeting between President Xi Jinping and Biden on November 16 and the confirmation by the US Senate of Nicholas Burns, Biden’s nominee to be ambassador to China. It is also worth noting that South Korean President Moon Jae-in said on December 13 that his country, North Korea, China and the US had agreed “in principle” to formally end the Korean war.

These positive factors will hopefully serve as brakes to stop the relationship going further downhill. However, right now, the downward momentum shows no sign of slowing any time soon.

The prevailing sentiment should be a bitter reminder to everyone of the wars, both hot and cold, of the past. Therefore, while people gather to celebrate the holiday season in both China and the US, we must all hope for better things to come in 2022.

The China-US relationship is a critical one for the world, and it has already descended a long way down a slippery slope. The most important task for each side in the years ahead is to take the likelihood of war, whether hot or cold, more seriously.

While Biden has made multiple public statements saying the US is not seeking conflict with China and does not want another Cold War, we must still be prepared in the event that things go wrong. The influence of the “three Cs” has already signalled the possibility of a costly US-China conflict.

Xu Xiaobing is director of the Centre of International Law Practice at Shanghai Jiao Tong University Law School