The shift emerged erratically. Division within the Trump administration on economic countermeasures against China prevailed for a time. Trump vacillated between criticism of China’s practices and avowed friendship with China’s leader Xi Jinping. Bipartisan majorities in Congress proved much steadier in establishing a “whole-of-government” US effort to counter China. The Trump administration’s punitive tariffs and restrictions on high technology sales to China resulted in a trade war until a truce in December 2018 led to talks resulting in a phase-one agreement in January 2020.

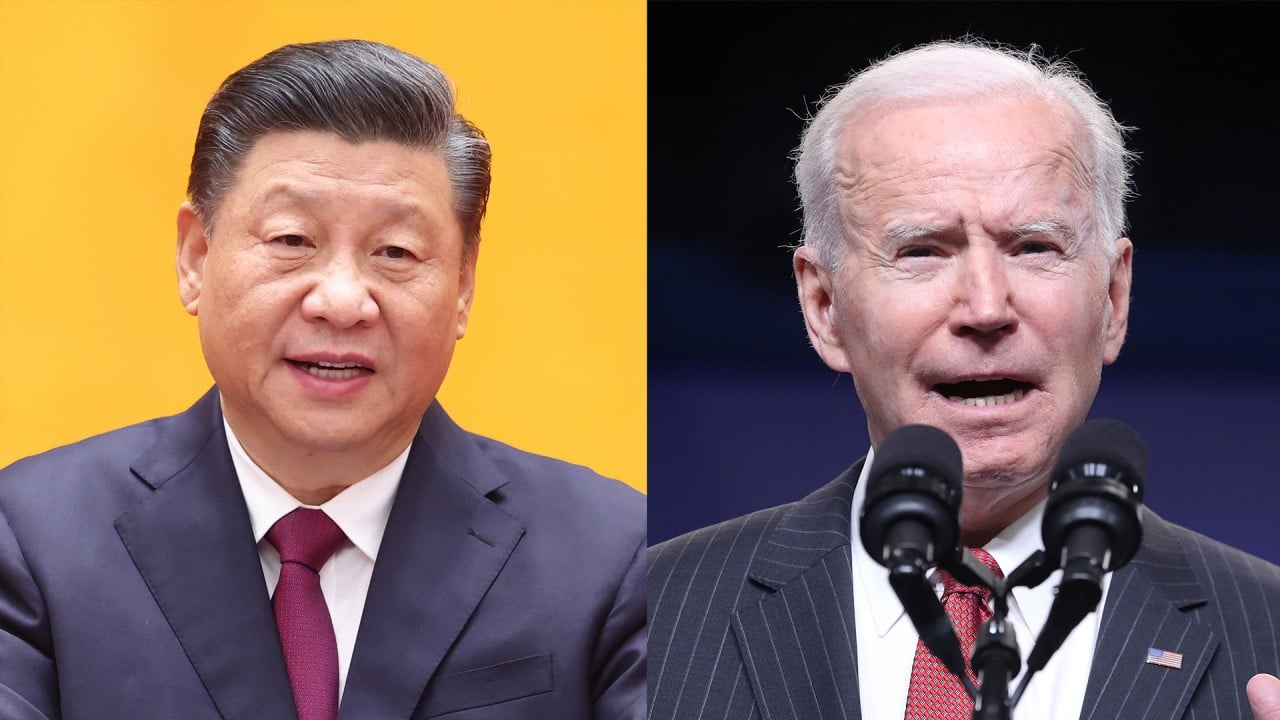

The negative shift against China ran up against US public opinion in 2019 which showed little support for a tough approach. Democratic presidential candidates infrequently discussed China, with Joe Biden prone to disparaging China’s capacities relative to the US.

SCMP Global Impact Newsletter

By submitting, you consent to receiving marketing emails from SCMP. If you don't want these, tick here

But a turning point came with strong American disapproval of the Chinese government’s behaviour as the Covid-19 pandemic hit the US in the midst of the presidential campaign of 2020. Both Trump and Biden emphasised toughness towards China.

00:54

US-China confrontation would be ‘disaster’, Xi says in first phone call with Biden

Changes under Biden

Biden took office amid a crescendo of the Trump administration’s anti-China actions designed to constrain moderation by the new administration. Congress remained steadfast as it held over many of the 300 legislative proposals targeting China at the end of the 116th Congress.

Biden warned against major dangers posed by China’s challenges, while Beijing advanced practices challenging American interests. Methodical statecraft resulted in strictures involving trade, human rights and other disputes with China. Substantial change in US strategy toward China awaited policy reviews that remained incomplete or unannounced after nine months in office.

Biden’s priorities in his domestic agenda focused on countering the pandemic, reviving the economy, reducing partisan government gridlock and mass protests undermining the democratic process, and protecting minority rights. His party had razor-thin majorities in Congress, placing a premium on gaining full support from all Democrats, including those who strongly opposed multilateral trade agreements and condemned authoritarian regimes abusing human rights and squelching popular democracy.

Coming second, foreign policy involved close cooperation with allies and partners, seeking multilateral solutions on public health, climate change and nuclear non-proliferation, and a priority to US interests in Asia. Interchanges with Chinese leaders came only after US consultations with allies and partners.

Competing with China in providing vaccinations abroad, the first summit between the Quad dialogue leaders from Australia, India, Japan and the US in March announced agreement to provide up to one billion doses of Covid-19 vaccine to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) countries and others by the end of 2022. China figured prominently in US discussions with the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato), the European Union, Japan, South Korea and Australia as US leaders asserted their intention to deal with China’s challenges from “a position of strength”.

Australian and British submarines in Perth, Western Australia. The Biden government’s resolve against Beijing’s challenges was underlined by the surprise announcement of the Aukus pact that will involve the sharing of nuclear submarine technology. Photo: EPA

Biden’s summits with the Japanese prime minister in April and the South Korean president in May resolved disputes over host nation support, dealt collaboratively with North Korean issues, and targeted China in referring to the South China Sea and Taiwan, the rule of law and freedom of navigation. Implicitly countering Chinese ambitions, the countries agreed to advance cooperation on new and emerging technologies in building more resilient supply chains.

US reassurance by Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan saw the Philippines carry out their most prominent rebuke of Chinese pressure tactics in many years. And Biden sent his close friend, former Senator Christopher Dodd, to show personal support for Taiwan’s president.

Biden warned that the main inflection point facing America is the fourth industrial revolution, with China confident that US democratic decision-making processes are less efficient and that its authoritarian system therefore will overtake America. He argued “we can’t let them win”.

The controversy surrounding the rushed US withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 undermined America’s position as a world leader and damaged Biden’s political standing. But the Biden government’s resolve against Beijing’s challenges was underlined by the surprise announcement on September 15 of a new US security relationship with Australia and Britain, named Aukus, that involves the sale of US nuclear submarine technology and closer collaboration in dealing with China.

Meanwhile, tensions in the Taiwan Strait rose with unprecedented shows of force by Chinese warplanes intruding into Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone.

01:04

Biden to approach US-China relations with ‘patience’, says White House

In Southeast Asia, America is losing

Despite the Biden government garnering support in its competition with China from Australia, India, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan as well as European and Nato partners, the competition is viewed warily in Southeast Asia.

China has distinct advantages with extensive borders with Southeast Asian neighbours and control of major rivers of utmost importance to neighbouring states. It is the largest trading partner and second largest source of financing for infrastructure in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asian states are deeply invested in China while China’s investment in the region has grown impressively over the past decade. China ably controls and asserts its claims to most of the South China Sea against much weaker capacities of Southeast Asian claimants.

China is widely seen as the engine of economic growth for the region. The Belt and Road Initiative provides much needed financing and construction capacity. The Chinese party-state’s overt and covert organs increase its influence over the ethnic Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia. China also works to establish its leadership through Confucius Institutes and student exchanges. Chinese tourists dominate this industry in Southeast Asia.

The US economic position in Southeast Asia has strong points too. US two-way trade with the region reached US$308 billion in 2020, and US investment in the region between 2015 and 2020 was US$111 billion, more than any other country. US ally Japan is among Asean’s largest trading partners and between 2015 and 2020 Japan put US$102 billion in FDI into Asean, more than China. Strategically, the US sustains alliance relations with the Philippines and Thailand, a significant military presence in Singapore, and active military exchanges with Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia. US forces guard against disruptive changes in the Indian Ocean approaches to the Malacca Strait and challenge China’s expansionism in the South China Sea.

An American aircraft carrier carries out joint exercises with Japanese vessels in the Pacific Ocean. Photo: AP

Nonetheless, American achievements fail to change the prevailing narrative in the region which views China as ascendant and the US in decline. In the recent past the US was seen as the region’s most important strategic power, but now China is seen as the most influential.

This shows in widespread criticism of US actions but silence on issues sensitive to Beijing. Chinese client states Cambodia and Laos block efforts by others to get Asean to defend Southeast Asian claimant states’ jurisdiction in their maritime zones against China’s nine-dash-line claim in the South China Sea. The claim was deemed illegal by an international law of the sea tribunal five years ago, but Beijing’s pressure means Asean generally avoids discussing the ruling. A decade ago, US observers commonly judged that talks between China and Asean on a code of conduct in the South China Sea would stabilise the situation in line with the interests of the Southeast Asian claimants and the US. Today, a common expectation is that China may so dominate the discussion that the code may well have provisions supported by China barring military activities by the US.

US policymaking is seen in Southeast Asia as devoting only episodic attention to the area. US internal problems depict a nation poorly positioned to lead abroad.

The US government does not have the funds to compete with the belt and road. Progressive Democrats oppose multilateral trade agreements, yet their support is essential for Biden’s domestic legislative priorities. As a result, it remains unlikely that the Biden government will join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership which Beijing now seeks to join, even though US membership of this trade pact would provide an economic programme attractive to the region and competitive with China.

Similarly, progressive Democrats and others in Congress demand US foreign policy emphasis on democracy and human rights, which is not well received by most regional states and limits US flexibility in dealing with the military junta in Myanmar.

Biden’s determination to counter China in Asia was reinforced by the surprise announcement of the Aukus pact. Yet, the initial reactions in Southeast Asia were of the Philippines being openly supportive, Malaysia and Indonesia publicly critical, and Vietnam and Singapore being ambivalent.

02:39

Once a symbol of promising US-China ties, Iowa house Xi Jinping stayed in 1985 now empty

Outlook

For now, the Biden administration seems determined to continue advancing relations with Southeast Asia in areas those governments believe will not upset Beijing. Some specialists argue the US has no choice but to stay actively involved as Southeast Asia is perhaps the world’s most important channel of international trade and the region is on track to become the world’s fourth largest economy. This view holds that outside countries capable of deepening their economic relationships in Southeast Asia will write the rules for future development, trade, and investment.

Over time, such an approach may win over Southeast Asian governments which reportedly register keen anxiety in private over the region’s growing dependence on and deference to China.

Indeed, China appears resolved in using a combination of blandishments and coercion in advancing control in regional affairs. And the US may come up with a strategy that meets the needs of the Southeast Asian states while also serving to counter Chinese challenges.

However, in this time of US preoccupation with domestic issues and blowback from the Afghanistan withdrawal, it is more likely that Biden will focus on working with partners to counter Chinese challenges, notably the Quad powers. Meanwhile, allowing Southeast Asia and Asean to face more directly the risks of Chinese dominance may incentivise some regional countries to take steps that will encourage the US to sustain strong relations with them in the interest of preserving their autonomy and rights.

Robert Sutter is professor of practice of international affairs at George Washington University, and was visiting fellow of ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute between July and September 2021. This is an excerpt of an article titled ‘Why US Rivalry with China Will Endure: Implications for Southeast Asia’, published in ISEAS Perspective 138